Part One: Seas Red and Black

Part Two: Riders Beyond the Silk Road

Part Three: In The Country of the Man-Eaters

Part Four: The Cross on the Ice

Part Five: The Outermost Ends of the Earth

After dwelling in the veritable hinterlands of the Far North - possibly even Scotland, since the opportunity and route was there - Andrew turned south towards "civilisation." Coming through what is now Poland, he may have encountered other tribes - the early Rugians, Burgundians, and Vandals, who would go on to cause so much trouble for the Romans in the coming centuries. Andrew was deep in the Country of the Barbarians, and far from home.

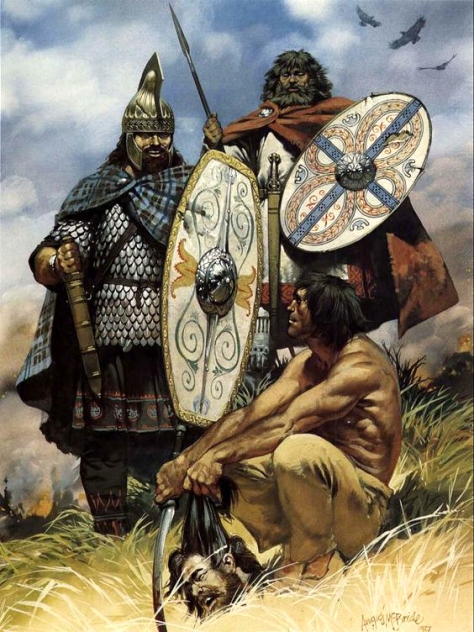

In Andrew's time, Slovakia, along with Poland, was part of what the Romans called Germania Magna - "Greater Germania" - a vast area beyond the limes (frontier) of the Empire. Only a few years after Andrew was born, the terror of the Germanians hit Rome like a ton of bricks at the Teutoberg Forest, as pictured above by the incomparable Angus McBride. Those borderlands in what is now Slovakia were roamed by the Quadi, who may have joined the Vandals on their migration to Iberia, and the Carpi, for whom the Carpathian Mountains derive their name:

The Narisci border on the Hermunduri, and then follow the Marcomanni and Quadi. The Marcomanni stand first in strength and renown, and their very territory, from which the Boii were driven in a former age, was won by valour. Nor are the Narisci and Quadi inferior to them. This I may call the frontier of Germany, so far as it is completed by the Danube. The Marcomanni and Quadi have, up to our time, been ruled by kings of their own nation, descended from the noble stock of Maroboduus and Tudrus. They now submit even to foreigners; but the strength and power of the monarch depend on Roman influence. He is occasionally supported by our arms, more frequently by our money, and his authority is none the less.

- Tacitus, Germania 42

... the Marsigni, Gotini, Osi, and Buri, close in the rear of the Marcomanni and Quadi. Of these, the Marsigni and Buri, in their language and manner of life, resemble the Suevi. The Gotini and Osi are proved by their respective Gallic and Pannonian tongues, as well as by the fact of their enduring tribute, not to be Germans. Tribute is imposed on them as aliens, partly by the Sarmatæ, partly by the Quadi. The Gotini, to complete their degradation, actually work iron mines. All these nations occupy but little of the plain country, dwelling in forests and on mountain-tops. For Suevia is divided and cut in half by a continuous mountain-range, beyond which live a multitude of tribes.

- Tacitus, Germania 43

After that, Andrew found a place which he would consider home for the next 20 years, in what is now Romania - a land the Romans called Dacia.

The Dacians were a people formed by the admixture of Thracians, Scythians, and Celts, forming a unique and sophisticated culture. Centuries before Andrew's time, the Dacians advanced from a tribal society to a fully-fledged nation state under King Burebista: they built highly complex urban centres, fortresses called "davas." Dacian goldsmiths were highly accomplished, with exports to Rome, Greece, and even Scandinavia. After Burebista's death, Dacia became a land divided among tribes once again, and would not be united until the reign of King Decebalus in 87 AD: After several successful victories over the Romans, Dacia became a client kingdom - an arrangement that was far more beneficial to the Dacians than to the Romans.

Dacian society was notable for its comparatively egalitarian attitudes. There were two social groups: the Cometai ("free people"), and Tarabostes (nobility), with the king directly elected by the nobility. Women had greater freedoms than their Roman or Hellenic counterparts, and slavery is poorly attested in comparison to other lands of the time period. A third group, the priesthood, coincided with the adoption of the Cult of Zalmoxis.

While travelling, Andrew followed an almost aescetic lifestyle of celibacy and strict vegetarianism, in the manner of John the Baptist. Owing to this hermetic existence, he tended to favour caves as his temporary shelters: there are many caves in Europe which are associated with him, such as the one above Lake Kremaston in Evrytania, Greece. There is a cave in Dervent, Dobrogea, in what is now Romania, which has become a holy site dedicated to Andrew. Andrew made this cave his home base for the next 20 years, sometimes travelling hundreds of miles away, but regularly returning here. Why here, specifically?

Andrew probably felt quite at ease with the Dacians. According to the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, their clerics were much like the Essenes of Judea: celibate, vegetarians - they didn't even eat fleshy vegetables, only seeds and nuts - and monotheistic, worshipping but one god, Zalmoxis.

The belief of the Getae in respect of immortality is the following. They think that they do not really die, but that when they depart this life they go to Zalmoxis, who is called also Gebeleizis by some among them. To this god every five years they send a messenger, who is chosen by lot out of the whole nation, and charged to bear him their several requests. Their mode of sending him is this. A number of them stand in order, each holding in his hand three darts; others take the man who is to be sent to Zalmoxis, and swinging him by his hands and feet, toss him into the air so that he falls upon the points of the weapons. If he is pierced and dies, they think that the god is propitious to them; but if not, they lay the fault on the messenger, who (they say) is a wicked man: and so they choose another to send away. The messages are given while the man is still alive. This same people, when it lightens and thunders, aim their arrows at the sky, uttering threats against the god; and they do not believe that there is any god but their own.

I am told by the Greeks who dwell on the shores of the Hellespont and the Pontus, that this Zalmoxis was in reality a man, that he lived at Samos, and while there was the slave of Pythagoras son of Mnesarchus. After obtaining his freedom he grew rich, and leaving Samos, returned to his own country. The Thracians at that time lived in a wretched way, and were a poor ignorant race; Zalmoxis, therefore, who by his commerce with the Greeks, and especially with one who was by no means their most contemptible philosopher, Pythagoras to wit, was acquainted with the Ionic mode of life and with manners more refined than those current among his countrymen, had a chamber built, in which from time to time he received and feasted all the principal Thracians, using the occasion to teach them that neither he, nor they, his boon companions, nor any of their posterity would ever perish, but that they would all go to a place where they would live for aye in the enjoyment of every conceivable good. While he was acting in this way, and holding this kind of discourse, he was constructing an apartment underground, into which, when it was completed, he withdrew, vanishing suddenly from the eyes of the Thracians, who greatly regretted his loss, and mourned over him as one dead. He meanwhile abode in his secret chamber three full years, after which he came forth from his concealment, and showed himself once more to his countrymen, who were thus brought to believe in the truth of what he had taught them. Such is the account of the Greeks.It's quite natural that Andrew would find the Dacians quite amenable to Christ - in fact, so taken were the Dacians with Andrew's teachings, Romanian tradition suggests that not only did they accept Christianity, they actually considered Christianity the natural extension of their existing religion.

- Herodotus, The Histories

Of course, the Dacians were no hippies: they were great warriors, too. Their signature weapon was the Falx, a great two-handed blade which was so devastating, it was once believed the Roman army had to institute running changes in their panoply while on campaign, as the famous lorica segmentata was particularly vulnerable to an armour-piercing terror such as this.

And, because we can never get away from those blasted dog-headed people, there are also legends a mythological relationship between the Dacians and wolves. Strabo claimed the Dacians were named Daï, or Daoi:

But there is also another division of the country which has endured from early times, for some of the people are called Daci, whereas others are called Getae — Getae, those who incline towards the Pontus and the east, and Daci, those who incline in the opposite direction towards Germany and the sources of the Ister. The Daci, I think, were called Daï in early times; whence the slave names "Geta" and "Daüs" which prevailed among the Attic people; for this is more probable than that "Daüs" is from those Scythians who are called "Daae," for they live far away in the neighbourhood of Hyrcania...

- Strabo, Geographica

Daoi, Dai and Daüs are very similar to the words for wolf in several neighbouring languages:

According to Strabo, the original name of the Dacians was daoi. A tradition preserved by Hesychius informs us that daos was the Phrygian word for "wolf.' P. Kretschmer had explained daos by the root *dhäu, "to press, to squeeze, to strangle."' Among the words derived from this root we may note the Lydian Kandaules, the name of the Thracian war god, Kandaon, the Illyrian dhaunos (wolf), the god Daunus, and so on. The city of Daous-dava, in Lower Moesia, between the Danube and Mount Haemus, literally meant "village of wolves. Formerly, then, the Dacians called themselves "wolves" or "those who are like wolves," who resemble wolves. Still according to Strabo, certain nomadic Scythians to the east of the Caspian Sea were also called daoi. The Latin authors called them Daliae, and some Greek historians daai. In all probability their ethnic name was derived from Iranian (Saka) dahae, "wolf." But similar names were not unusual among the IndoEuropeans. South of the Caspian Sea lay Hyrcania, that is, in Eastern Iranian "Vehrkana," in Western Iranian "Varkana," literally the "country of wolves" (from the Iranian root vehrka, "wolf'). The nomadic tribes that inhabited it were called Hyrkanoi, "the wolves," by Greco-Latin authors. In Phrygia there was the tribe of the Orka (Orkoi).

We may further cite the Lycaones of Arcadia, and Lycaonia or Lucaonia in Asia Minor, and especially the Arcadian Zeus Lykaios" and Apollo Lykagenes; the latter surname has been explained as "he of the she-wolf," "he born of the she-wolf," that is, born of Leto in the shape of a she-wolf. According to Heraclides Ponticus (Fragm. Hist. Gr. 218), the name of the Samnite tribe of the Lucani came from Lykos, "wolf." Their neighbours, the Hirpini, took their name from hirpus, the Samnite word for "wolf." At the foot of Mount Soracte lived the Hirpi Sorani, the "wolves of Sora" (the Volscian city). According to the tradition transmitted by Servius, an oracle had advised the Hirpi Sorani to live "like wolves," that is, by rapine. And in fact they were exempt from taxes and from military service, for their biennial rite-which consisted in walking barefoot over burning coals-was believed to ensure the fertility of the country. Both this shamanic rite and their living "like wolves" reflect religious concepts of considerable antiquity. There is no need to cite other examples. We will note only that tribes with wolf names are documented in places as distant as Spain (Loukentioi and Lucenses in Celtiberian Calaecia), Ireland, and England. Nor, indeed, is the phenomenon confined to the IndoEuropeans.

The fact that a people takes its ethnic name from the name of an animal always has a religious meaning. More precisely, the fact cannot be understood except as the expression of an archaic religious concept. In the case with which we are concerned, several hypotheses can be considered. First, we may suppose that the people derives its name from a god or mythical ancestor in the shape of a wolf or who manifested himself lycomorphically. The myth of a supernatural wolf coupling with a princess, who gives birth either to a people or a dynasty, occurs in various forms in Central Asia. But we have no testimony to its existence among the Dacians.

- Mircea Eliade, Zalmoxis, the Vanishing God

On top of that, there is the legend of the Great White Wolf, the Right Hand of Zalmoxis, which was later combined with Saint Andrew in Romanian tradition:

Before the Great White Wolf, there was a man, a young man that in spite of his age had a long white beard and white hair. He wandered the land of Dacia, helping people and preaching the word of Zamolxe. He found shelter in a cave in the mountains where he enjoyed the love and respect of the animals. Out of all the creatures of the forest, the wolves where the ones that loved him the most. He taught the wolves to respect men and not attack them and their households. The man also taught the Dacians to care for the wolves and give them food while the wolves helped and fought with them in battle. Thus, man and wolf became brothers.Between the Cynocephalae and the Neuri, I'm starting to wonder if Andrew actively looked for wolf-people!

Zamolxe, knowing that danger was to come over Dacia he asked the white bearded man if, in exchange of immortality and a place by his side in the Sacred Mountain, he wants to become the leader of the wolves. Exchange that the white bearded man, out of loyalty and love for Dacia, gratefully accepted. Zamolxe turned him in the Great White Wolf. Together they watched over Dacia, Zamolxe as the leader of the people and the Great White Wolf as the leader of wolves.

For centuries their land was prosperous and peaceful but, as history showed us, it was not bound to last. The Romans were getting nearer and nearer and some of them managed to poison the mind of men against their brother wolves. So the Dacians started hunting them with the belief that, if they killed the Great White Wolf and brought its head to the Romans, their land would be spared a war.

The wolves, betrayed, retreated deeper into the forests and never came out. The Great White Wolf retreated alongside Zamolxe to the Sacred Mountain and watched how war and misery took over their land. The Dacians, having lost the loyalty of the wolves received no help from them during their battles with the Romans. This is how Dacia became a Roman province.

A sad coda to the story of the Dacians came only decades later. The new Emperor, Trajan, needed resources for a rapidly expanding empire. The Dacians had great wealth in gold mines, but were hardly going to simply give it away to Rome. Trajan decided to deal with the Dacians in a rather permanent way - by utterly destroying the kingdom. Trajan sent 150,000 legionaries across the Danube to punish the Dacians: the peace treaty was so ruinous that a second war was waged. This time, Trajan sent 200,000 legionaries, and there would be no truce. Trajan razed Sarmizegetusa. Tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of Dacian men were taken as slaves. The southern portion of Dacia became a Roman province: the north became a wilderness of "Free Dacians" - never united, but at least they were free.

Trajan's conquest was popular and well-received - as were the thousands of tons of gold & silver looted from Dacia. Trajan's Column was commissioned as a monument to that bloody and violent campaign:

Many of the images on Trajan's Column depict Romans slaughtering Dacians. It is ironic that we are left with so many contemporary images of a Barbarian people about whom we otherwise know so little. The Column celebrates Trajan's campaign in AD 101-6, in which he entered the kingdom of Dacia and destroyed the entire Dacian nation. Or at least that's what the Romans liked to think.

Nowadays some historians are reluctant to accord Trajan the honour of achieving total genocide. They point to inscriptions and written documents that indicate sufficient Dacians escaped the Roman holocaust to have ensured some continuity from those days to the present, when what remains of the country of Dacia is known - ironically enough - as Romania. There are records, for example, of at least 12 units of Dacian soldiers being subsequently posted to various parts of the Roman Empire - many of them, according to the archaeological record, to Britain. What's more, the Column itself concludes with an image of Dacians peaceably returning to graze their sheep on the emptied land.

The snag is that in ancient Rome it was common knowledge that Trajan had annihilated the Dacians. The Emperor's doctor, Crito, claimed that Trajan had done the job so well that only 40 Dacians remained - at least that's what the writer Lucian said he said. Crito did write an account of his adventures in Dacia with Trajan, but the book is now lost, and Lucian, who was a satirist and wit, may have been employing comic hyperbole to make a point.

But later writers continued to perpetuate the idea. They included the Emperor Julian (better known as Julian the Aposstate) who, in one of his works, imagines Trajan announcing: 'Alone, I have defeated the peoples from beyond the Danube and I have annihilated the people of the Dacians.' The fourth-century historian Eutropisu wrote that, when Dacia had been defeated, all that remained was a wasteland that Trajan then repopulated with people from various other parts of the Empire. "Trajan brought countless masses of people from the whole Roman world to live in the fields and in the cities, since Dacia was exhausted of men after the long war.

Since this was a widely known story, it could well be that the last images on Trajan's Column depict not the return of Dacians to their native soil, but the repopulation of the empty country by Roman settlers. It has also been suggested, however, that the images may be of Dacians being relocated in the Empire.

As for the deployment of Dacians in the Roman army, that too could be taken as a sign that very few Dacian males were allowed to remain in the country after the campaign. Another writer, who based his information on Crito's account, claims that Trajan pressed half a million Dacians into the Roman army. Although this is probably an exaggeration, it indicates that the Romans were determined to leave very few males on their native soil - a fact confirmed by Eutropius.

One archaeologist, Linda Ellis, describes it as a kind of Year Zero, with the Romans wiping Dacia clean and building a new civilisation as though this were terra nova, new land. "There was no continuation of Dacian traditions, either religious tradition or economic or political tradition, so Dacian civilization had been literally wiped from the surface and a new Roman order had been emplaced upon it." Whether they killed off the entire population or not, the Romans did a thorough job of removing Dacian culture and identity from the world map.

The Dacians, then, have the distinction of being one of the few nations on earth whose destruction has been lovingly recorded in pictures for posterity.

- Terry Jones, Barbarians

Trajan's campaign was the bloodiest since the destruction of Carthage, and enacted a wholesale elimination of a culture's very existence. Such a fate is usually ascribed only to the very strongest of Rome's enemies - not only must their power be broken, but their very identity. Yet Romanian national pride has not forgotten the people of Dacia: whether the Romanians of today share ethnic roots with the ancient Dacians or not, there is a kinship born of a shared love of their homeland and appreciation of their history - not unlike the one we Scots have for the ancient Caledonians, who (tradition tells us) were destroyed by our ancestors. Sometimes the reality is kinder than the myth.

Part Seven: "This Day A Martyr Or A Conqueror!"

Part Eight: Martyrdom in the Land of Lost Gods

Part Nine: The Scotland Yet To Come

Add Comments